by: Steve Hargreaves

A new proposal to curb global warming could jump start stalled Senate greenhouse gas discussions and put an average of $1,100 a year back into the pockets of American consumers.

Known as cap-and-dividend, the recently introduced bill would require oil, coal, and natural gas companies to buy permits each month to sell their fuel. Three quarters of the proceeds would be returned to the public each month in the form of a dividend check, with the remaining money going towards renewable energy, conservation or assistance programs.

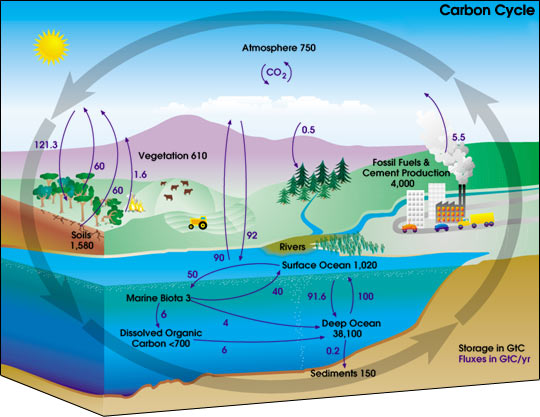

By driving up the cost of fossil fuel and making renewables more competitive, supporters say the plan will result in the same emission reductions as the current cap-and-trade bills before Congress. But they say it will be much more simple to operate.

"The act provides businesses and investors with a simple, predictable mechanism that will open the way to clean energy expansion while achieving America's goals of reducing carbon emissions," Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., said in a statement announcing the bill earlier this month.

But critics fear the bill may stifle innovation. By limiting Wall Street's role in the trading of carbon credits they fear new technologies will die on the vine, missing out on needed capital from the investment community.

Currently, the most talked about method of reducing greenhouse gases is through a cap-and-trade plan. Under it, power producers and other large emitters of carbon dioxide would be required to obtain permits each year from the government. Those permits would decline in number annually - hence the cap. The industries could either pay to clean up their operations, or buy the permits from one another - hence the trade. A version of this plan has passed the House, and one has been introduced in the Senate as well.

It's a complicated system that critics say is too compromised. To woo votes, sweeteners were thrown in for just about everyone: Farmers are allowed to make money selling carbon offsets, the coal industry was cut a break, Wall Street is allowed in on the trading.

The main difference between cap-and-trade and the new cap-and-dividend idea is the cap-and-dividend cuts out the trade part, and with it the Wall Street traders.

While consumers will see their gas or electricity prices rise, supporters say cutting out Wall Street will prevent speculators from driving up the cost of carbon credits just to make a buck, and ultimately save consumers money.

0:00 /7:27Nobel advice for saving the planet

A staffer for the bill's other sponsor, Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, said that after receiving some $1,100 in rebate checks each year and paying higher gas and electric prices, the average Maine consumer would come out $102 ahead.

While savings or costs for cap-and-dividend will vary from state to state, the Congressional Budget Office estimates a cap-and-trade plan would cost consumers $175 a year on average nationwide.

Roughly 80% of the population would end up either breaking even or making money under cap-and-dividend, said the staffer. The remaining 20%, generally wealthier people who use more energy in things like multiple dwellings and air travel, would lose money.

"Climate change legislation must protect consumers and industries that could be hit with higher energy prices," Collins said in a statement.

The Democrats in the Senate are having a rough time mustering enough support to pass the bill even within their own party. Many Senators fear the legislation will be too costly for their constituents.

Getting the Senate to pass a bill, and ultimately have the United States enact mandatory cuts in greenhouse gases is seen as essential in securing a new worldwide global warming treaty.

What about Wall Street?

But cutting out Wall Street may have its downsides.

Allowing trading in carbon credits enables businesses to monetize those credits, in effect creating wealth, Kevin Book, a managing director at ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington, D.C.-based firm that tracks political developments in the energy sector, said in an analysis of the bill.

[Cap-and-dividend] would transfer wealth within the economy, whereas [cap-and-trade] would inject $1 trillion of wealth into the economy," said Book.

And unlike simply giving the money to consumers, cap-and-trade directs much of the money to agriculture and industry - constituents Book believes are essential if any global warming bill is to pass Congress.

"Passage of a cap-and-trade bill with industrial stimulus overtones remains more likely than a carbon tax of any kind," said Book.

And despite widespread public mistrust of Wall Street trading, especially when it comes to energy prices, there are still those that believe having the most players in the market is the best way to ensure greenhouse gases are cut for the cheapest price possible.

Allowing trading in carbon credits will let more capital flow towards this sector, said Paul Smith, chief risk officer at Mobius Risk Group, a firm that advises energy producers and big energy consumers.

More capital means more creative ways to cut greenhouse gases may emerge.

"You really need to let it be a free market," said Smith. "If the number of participants is limited, innovation is going to be limited as well."